“Here are the bright and passionate crops of wheat, aerial vine, hemp, an expanse like a sea” ( G. Raimondi, Notizie dall’Emilia, Einaudi 1954)

The history of the Villa

In the 1600s, all around Villa L’Ariosto existed only countryside as far as the eye could see, faint traces of dirt roads and in the distance a ribbon of trees that still like soldiers on a picket line watch the flowing waters of the Idice River, making it detectable in a bountiful plain.

Villa the Ariosto, the origin of the name – 1590

The search for the origin of the name given to the villa goes back to the earliest information found, more specifically, the purchase of “a prediolo, with house, threshing floor, well, oven and attached stable” made in 1590 by Cassandra Gaddi, widow of Ettore Ariosti.

The prestigious name of the Ariosti family, which owned the Villanova and Marano estate for only 37 years, became a toponym “of Ariosto’s places” even after the subsequent sale to wealthy timber merchant Marcantonio Pederzani in 1627.

The Ariosti were one of the oldest families in Bologna, named after the town of Riosto near Pianoro where they owned land and a castle. Its members included clergymen, politicians, men-at-arms, university professors and men of culture. Corradino Ariosti, of the Order of Preachers, promoted the construction of St. Dominic’s library in 1400 and was proclaimed Blessed for his intense religious life.

The family in the sec. XIII split into two branches, Bonifazio gave rise to the Ferrara branch from which the famous scholar Lodovico would be born in 1474, while his brother Tommaso continued the main and wealthy Bologna branch.

Villa Pederzani, from Manor House to Holiday Palace – 1627

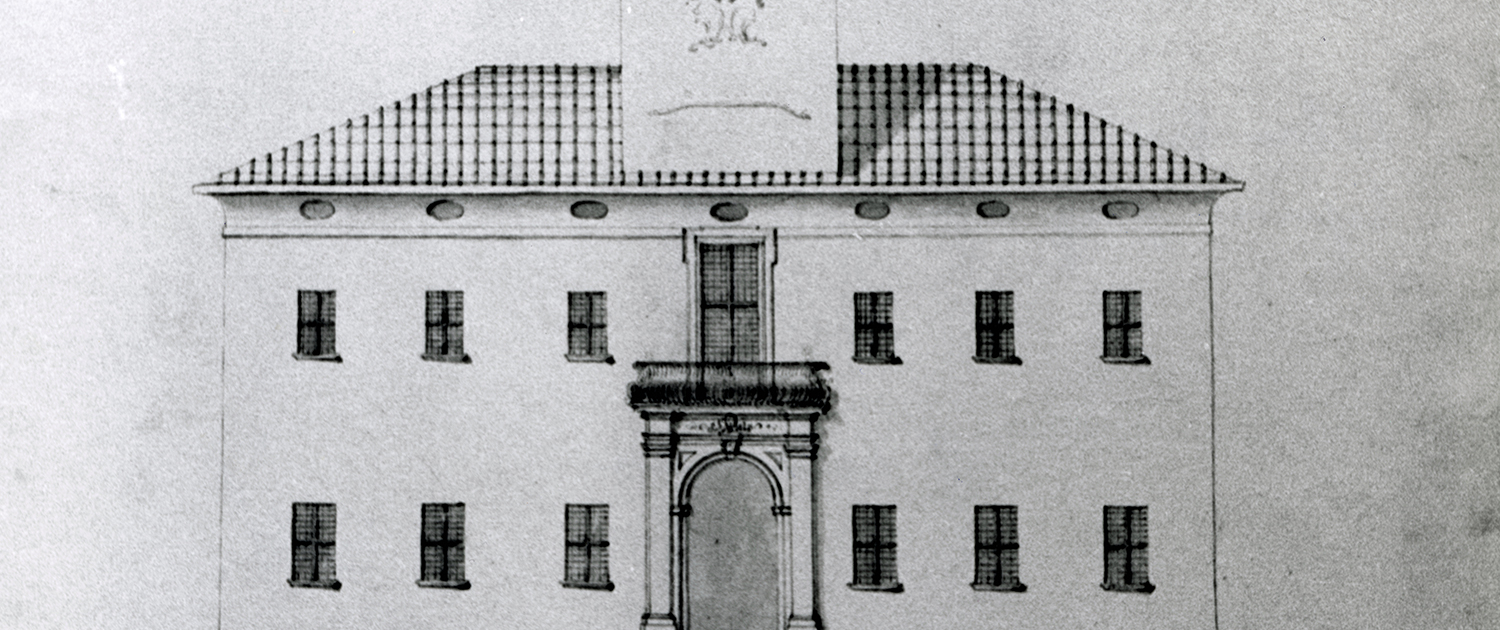

After the purchase in 1627, Marcantonio Pederzani transformed the manor house into a proper holiday palace, as was in use among the noble families of the sec. 17th century: the typical three-pitch roofing of farm houses in the Bologna area was converted to a four-pitch hipped roof, allowing for a fully habitable second floor and a service attic. An adjacent wing was built to the east, containing the farmer’s house and a shed. The dovecote tower characterized the building’s elevation.

The plague of 1630 probably delayed the completion of the transformation, but by 1632 numerous painters were already frescoing the building’s interior, giving it the connotation of a stately palace.

Villa Orsi and the construction of the theater in the west wing – 1694

Later, the villa was inhabited by Marquis Giovanni Giuseppe Felice Orsi, who became its owner in 1694 after leasing it for several years. He was responsible for the construction of the west wing of the villa, symmetrical to the pre-existing east wing, in which there was a small but rational theater and a small private chapel. This wing collapsed during one of the bombings in April 1944 and was never rebuilt.

Guests at the villa delighted in theatrical performances that enlivened the summer holiday season. Marquis Orsi was a prominent figure in Bolognese society at the time; he was a cultured, refined man and cared for the study of literature. His passion for theater led him to perform with ladies and knights within the private homes of Bologna, which at the time frequently had a theater, and he established an Academy in his own home where twice a week erudite discussions of Poetics and Eloquence took place, ending with a sumptuous dinner. Marquis Orsi died in 1734 at the age of 82; throughout the Italian peninsula his value as a man of genius and culture was recognized, and he was honored by Pope Clement XI, the Duke of Parma, other princes and cardinals, and almost all the Academies of Italy. The clear fame, which had accompanied him in his time, was not immortal because, today, he is a figure whose memory has unfortunately been lost.

Palazzo Conti i.e. the transformation of the pigeon tower into a specola or belvedere – 1740

In 1718 L’Ariosto was purchased by Matteo Conti, a wealthy bourgeois family with countless properties in the city, and from then on the villa was identified on maps as Palazzo Conti. He was responsible for the transformation, carried out in 1740, of the pigeon tower into a specola or, more simply, a belvedere. Some plans for this intervention are preserved in the villa, although they differ from what was actually carried out. The specula is connoted by an elegant and large serlian window, to maintain greater congruity with the style of the villa and its purpose as a summer home.

Villa Silvani, the making of the hall – 1820

In 1820 the villa was purchased by the lawyer. Antonio Silvani, a distinguished jurist, university professor, patriot and statesman. He participated in the Risorgimento uprisings of 1831 and served as Minister of Justice in the Government of the United Provinces, but when the revolution failed he was imprisoned by the Austrians and forced into exile in Paris and Lucca. In 1846 he received an amnesty, was reinstated to his university professorship and, together with Marco Minghetti, was appointed a member of the Consulta di Stato established by Pius IX to represent Bologna. The following year he died suddenly in Rome.

After purchasing the mansion, Adv. Silvani had a salon made, merging the two salons located to the northeast. The load-bearing wall that divided the two rooms was replaced by a segmental arch, covered by a pavilion vault made of arelle and plaster, finely decorated in the manner of Giani; an original space of the villa’s interiors. The construction of the vault has concealed from view the wall friezes and 17th-century coffered ceilings, which today remain partially visible from a small closet above.

Abandonment – 1945 to 1981

The descendants of Adv. Silvani held prestigious positions in the university and city institutions until the last descendant Paul, who was born in 1881 and died in 1945.

The latter was a board member of the University, numerous public corporations and Opere Pie, and was a member of the Deputation of Local History, the Academy of Agriculture and cultural institutes.

All the Silvans were very attached to the palace at Villanova, where they spent the summer months. Only Paul designated the mansion as his permanent home and, for him, it was a hard blow to witness its partial destruction and devastation due to the war. It is said that these events were a concomitant cause of his death from heartbreak, which occurred in June 1945.

In 1943, a Germanic military command had occupied the villa, but the Allied bombing raids, which hit the area hard and repeatedly in 1944, probably had the nearby Marano powder magazine and the adjacent San Donato railroad yard as their main targets.

It is not known precisely which of these air raids hit the villa, destroying the west wing, and the forest to the north, leaving craters still visible when restoration work began in the early 1980s.

The mansion, thus damaged and defenseless, became the object of looting and vandalism: all wood paneling, furniture and parquet floors were torn up and burned.

Upon the death of his brother Paul, his sister Maria, the only surviving member of the family, attempted to prevent the villa’s deterioration. He rebuilt in the rough the damaged wall bordering the theater, which was destroyed by bombs, relocated the fixtures to the ground floor windows to prevent further devastation.

Thus the villa became a place of shelter for homeless families and, later, was frequented by Castenaso’s youth to meet and dance inside the lodge. It was no longer inhabited. Only the settler Duilio, who had spent his life on the Silvani property, continued to occupy the farmer’s house, in the few rooms that were not damaged, as a shelter and resting place on days spent cultivating the surrounding fields.

In 1964 Maria Silvani died, ending a bourgeois dynasty that had lived in Bologna for 150 years, excelling in culture and civic and civic engagement. After a few years, Ballarini’s heirs put the villa together with the funds up for sale, but it remained unsold until June 19, 1981, when Franco Manaresi bought it, deeding the bare ownership to his children Giovanni, Stefano, Nicolò and Carolina Manaresi.

Restoration

In 1981 the mansion presented itself to the visitor in complete and melancholy disrepair: the plaster and gutters were falling off, the arelle cornice gutted, the walls overgrown with weeds, a once manicured forest of delight had been transformed by the growth of brambles into an inaccessible place.

The interior of the mansion was even more bleak and dingy, a tractor and other farm implements were in the center of the loggia, the walls were peeling from rising damp, the cornices and stucco in pieces; the doors, frames and stained glass in the loggia were totally absent. The second floor lacked glass, and the shutters were the only barrier protecting the interior even though some of them had been damaged by woodpeckers and dormice that had turned some rooms into winter dens where they accumulated acorns brought from the garden. The west wall was still in the rough, the existence of an ancient electrical system was revealed by pieces of wire falling from the ceiling and ancient porcelain insulators still nailed to the walls. The attic was in even worse condition, masonry and framed partition walls were in disrepair and filled the floor with debris; the roof structure deteriorated so much that it was propped up in several places. The only toilet was a drop latrine with an underlying cesspool located under the staircase. The finishing touch to this distressing desolation was provided by seeing sudden movements of rats running along the frieze frames, the villa’s uncontested masters for nearly four decades.

Only the frescoes on the ground floor, covered with cobwebs that like black drapes enveloped them, held colors and images that were waiting to be revealed to revive the history that the mansion held.

Despite the decay, squalor, and collaborative cover, the villa manifested good structural stability, while the adjacent “Farmer’s House,” the eastern body, was in complete ruin.

Having carried out a survey of the building and obtained approval of the intervention project from the Superintendence for Environmental and Architectural Heritage of the Municipality of Castenaso, work began in the spring of 1983.

After some emergency work was carried out, recovery work progressed systematically until it was completed in May 1987. The complete reconstruction of the roof, done entirely in lumber, was followed by the consolidation of the attic floor and the restoration of the farmer’s house. The phases of the four-year restoration presented challenges of complex solution while continuously and consistently respecting the soul of the villa and its long history.

Between 2001 and 2005, the “Casa del Cocchiere” was reconstructed. A small building used as a stable, carriage house and coachman’s dwelling, located east of the “Farmer’s House”

After forty years of total neglect, a monument that we consider important for the works of art it contains, the historical memories of the families and personalities who owned it, has come back to life.